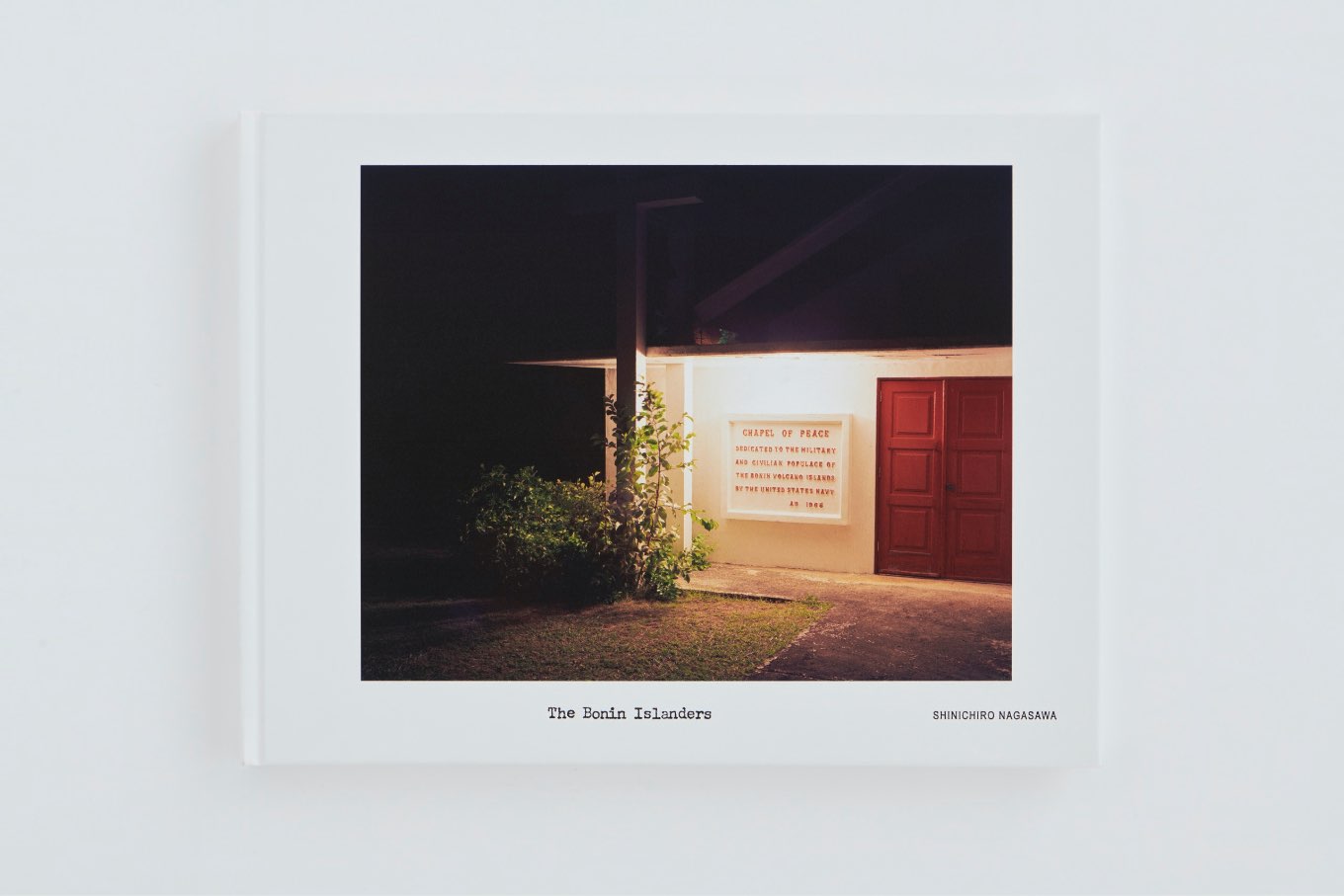

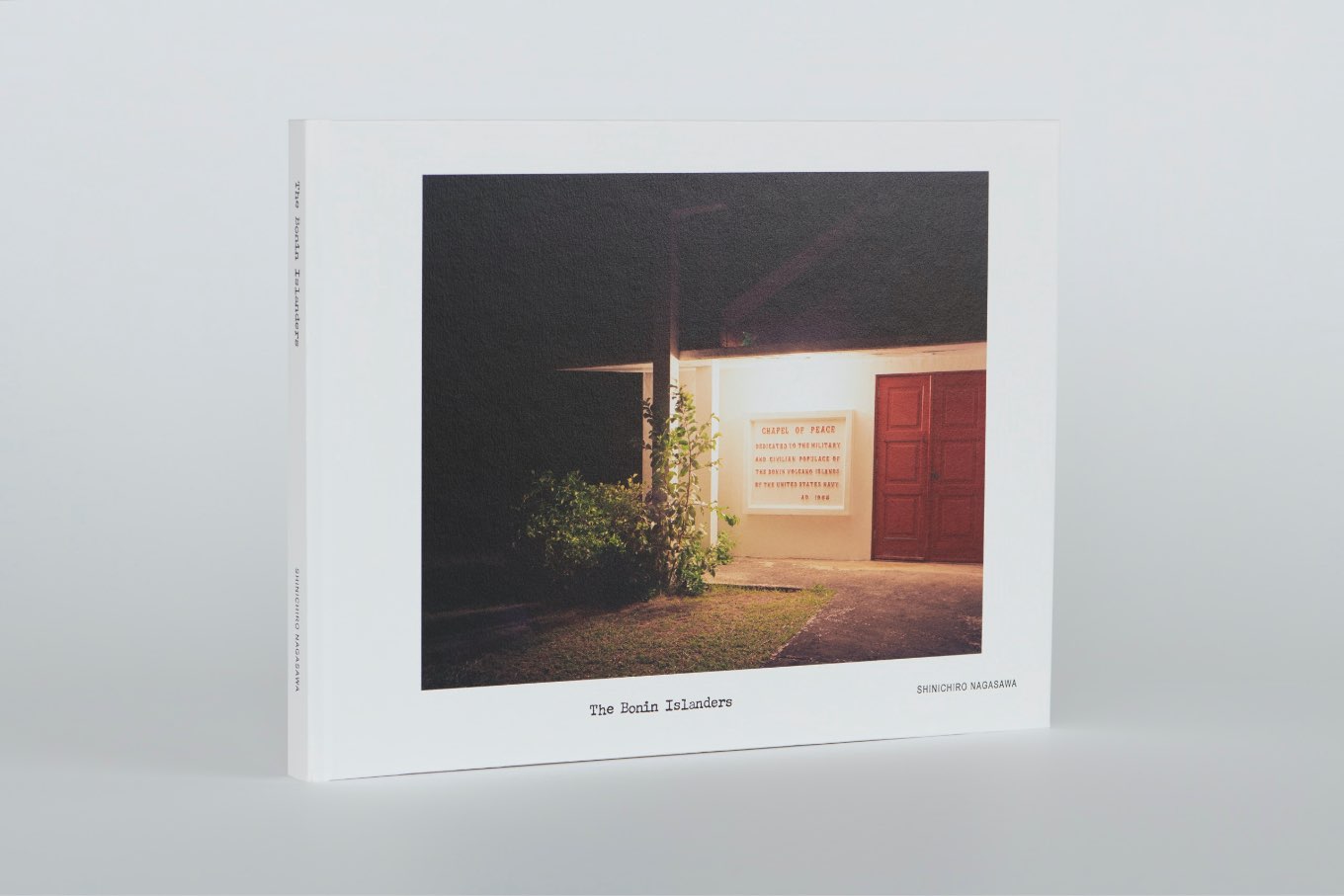

赤々舎 / 2021年5月19日初版発行 / 128ページ / ISBN978-4-86541-137-9C0072 / 寄稿 デイビッド・オド / デザイン 林規章

Akaaka Art Publishing,Inc. / First Edition 19 May, 2021 / 128pages / ISBN 978-4-86541-137-9 C0072 / Text David Odo / Design Noriaki Hayashi

<オンラインでのご購入>

オンラインショップ

https://shinichiro-nagasawa.stores.jp/

赤々舎ウェブサイト

http://www.akaaka.com/publishing/the-bonin-islanders.html

長沢が撮った小笠原

デイビッド・オド

ハーバード大学美術館 学術・公共プログラムディレクター、リサーチキュレーター

この写真集は、東京在住の写真家長沢慎一郎の、十年以上の長きに渡る小笠原諸島での撮影の集大成だ。欧米では「ボニン・アイランズ」として知られる小笠原諸島は、東京のおよそ千キロ沖に位置する大小三十余りの島々から成る群島。亜熱帯の島々の自然美は日本国内はもとより海外からも多くの観光客を惹きつけ、2011年には稀有で独特な(そしてよく保たれた)自然環境から、日本で四箇所目の(そして未だ四箇所しかない)世界自然遺産に登録された。小笠原の生態系にはオガサワラオオコウモリや、他では見られない鳥類や植物などの多くの絶滅危惧種が含まれ、群島を取り囲む海には幾種類ものサンゴや魚や鯨、その他の海洋生物が数多く生息している。

長沢も、これら豊かな自然環境を撮影している。しかし、彼の写真の真骨頂は美しいビーチや草花ではなく、2008年から通い続けた小笠原諸島の各地や人々との深い交流の轍にある。2007年、長沢は旅行雑誌で「欧米系移民」と呼ばれる人々(19世紀から20世紀に外国から移住してきた欧米人を祖先に持つ島民)の特集を読んで小笠原に興味を持った。19世紀当時から小笠原諸島はヨーロッパやアメリカ、そして日本の船乗りや捕鯨者たちの間で知られていたが、島に最初に定住したのは太平洋、アメリカ、ヨーロッパの出身者たち。当時は無人島だった小笠原諸島に捕鯨コロニーを作るため、1830年にホノルルを発った面々だった。ホノルルで作られたコロニーは、英国から経済的支援を受けていたものの属領にはならず、したがって、強国からの軍事的支援のないまま、当初は海賊からの頻繁な攻撃に脅かされていた。その後、島には日本を含む他国からも移住者が集まり、1870年代には新生の明治政府から国土指定される。第二次大戦中は1944年まで米軍と日本軍の陸戦場となり、戦後は1968年に日本に返還されるまで米軍の占領下に置かれた。小笠原は現在は東京都の管轄下にあり、(非常に)離れた都の島嶼部の一つになっている。ここは、ホモジーニアスと(誤って)表現されることの多い日本社会の中にある多民族コミュニティーであり、長沢が島民に興味を持ち、外部にほとんど知られていない彼らの物語を知りたいと思ったのは、何も驚くべきことではない。

2008年2月、長沢は東京と父島(旧名“ピール島”)の二見を結ぶ客船「小笠原丸」で父島に向かった。父島は小笠原村の中心的機能を果たす島で、二千五百人弱と言われる全村民のうち凡そ二千人が暮らしている。この島に千人の乗客を運ぶ小笠原丸での船旅は、通常二十五時間を要する。二見港に入港した船は数日そこに留まった後、船首を回して東京に戻る。そしてそれを繰り返す。小笠原には民間機用の空港がなく、船が本土と島々とを定期的に結ぶ唯一の移動手段だ。島ではしばしば船の一往復、すなわち二、三日を一単位に時間が数えられ、訪問者は「一航海の滞在か、それ以上か」と聞かれたりもする。長沢は、満を持して三航海分の滞在予定で小笠原に向かった。欧米系移民のコミュニティーに面識を得て、写真撮影をするのにも十分な期間のはずだった。しかし、彼の目論見は外れた。

長沢が最初に出会ったのは、南スタンリー、ホエール・ウォッチング船のオーナーかつ船長だった。父島に降り立った長沢は南氏に自己紹介し、欧米系先住民の歴史について知りたいということ、彼らの写真を撮りたい旨を伝え、そして即座に拒絶された。「帰れ!我々は晒し者になるためにここに居るんじゃない。我々はアメリカ人ではない。日本人でもない。小笠原人(Bonin Islanders)だ。興味があるだって?そんな理由で写真を撮るためにウロつかれても迷惑だ!」

幸先は悪かった。しかし結果的にはこれが、写真家には重要な教訓になった。長沢は、この最初の不運な巡り合わせによって、撮影は思っていたよりも複雑で時間のかかるものになりそうだと腹を括った。幸いにも彼はすぐに協力的な人物にも出会い、そのうち何人かは写真撮影にも快く応じてくれた。彼らによると、島民の写真撮影を巡ってはこれまでに何度もトラブルがあった。記憶に新しいところでも、欧米系移民が人格を持った人間としてではなく、標本や科学研究の対象のように扱われるケースが何件かあったという。ドイツ人遺伝学者による1927年と1957年は、「異人種交配」または「混血」と、彼らの形質特性についての画像証拠を作成することを目的にしており、当時の科学的人種差別を象徴するようなものだった。この研究は、当事者として撮影を覚えている年長者や、親族や友人がかつて被写体になったという若い世代を長い間苦しめ続けた。そして、この研究に写真が深く関与したことで、島民の心には写真への拭い難い不信感が植えつけられた。ただし、この研究さえも写真の(誤った)使用がボニン島民の心に写真不信を植え付けた最初の例ではなく、また最後の例でもない。

島々と写真を巡る歴史は、日本と小笠原島民の交流の最初期に遡る。最初に写真が撮影されたのは、日本が植民地探査を行った1875、76年。この探査は、短期かつ不成功に終わった江戸最晩年の1862年の入植の試みに続くものだった(この時には写真は撮られていない)。明治初期の探査で政府は公式に写真家を採用し、東京在住の商業写真家・松崎晋二が撮影に当たった。これ以降、日本は第二次大戦の終盤まで島々を治め、小笠原は戦後1968年に返還されてから今日まで日本領となる。お雇い写真師の松崎は、政府の情報収集目的にも日本国内向けの販売用にも写真を制作した。この時に作られた小笠原の風景と、とりわけ小笠原人の写真は、土地と人間に関する純粋なポートレイトというよりは、あくまで日本の新しい植民地に関する(植民地で新たに獲得した土地と人間に関する)、人間味のない画像資料として閲覧された。撮影時の条件の詳細は不明だが、植民地での初めての写真撮影だったことを考えると、島民には「どのように」はおろか、そもそも撮影可否についてさえほとんど発言の余地は与えられなかったと想像される。

日本の入植が成立した後は、政府、科学者、メディアなどが更なる撮影プロジェクトを進めた。表向きには現地の動植物の研究を謳うものもあったが、実際には島民、とりわけ欧米系移民の写真を含むものが多かった。島民の写真は、大正天皇のために作られたアルバムにも収められており、傍らには排斥的ないし人種差別的なキャプションが添えられた。母親と子供の写真には「南洋土蕃帰化人(南洋からの島民化した野蛮な帰化人)」とある。小笠原を題材に20世紀前半に作られた写真葉書の多くも欧米系移民を被写体にしているが、彼らは日本人移住者とは区分され、異邦人として紹介された。戦争の火の手が小笠原に迫り、戦局がいよいよ悪化した1944年には、日本政府により島民は本土に移住させらた。しかし、欧米系移民(と彼らの日本人配偶者・子供)は、1946年にアメリカに対して小笠原への帰還を嘆願している。本土で「ガイジン」と見なされて受けた差別があまりにも酷かったためだ。日本国籍にもかかわらず、本土で敵国人米人と誤解されて酷い差別を受け、国中が食料や衣類や住居などの物資難に陥って困窮した戦中戦後には、激しい略奪にも喘いだ。

日米両政府が小笠原諸島の日本返還計画を進めていた1968年、一人の年長の島民がある新聞記事で、自分たちが「南海のアイヌ」になる危険性を訴えている。自分たちが政府や、今後島を訪れる人たちから、排斥されたり異邦人として物珍しがられたりする惧れがある、と。写真が、島民をモノ化するのに利用される危険性は非常に高かった。

その後何年も、本人の許可(や何がしかの補償)なしに欧米系島民が撮影される例が後を絶たず、島民の心にはカメラを振り回す部外者への不信感が募った。長沢は二見港に降り立った時点ではこの史実を知らなかったが、南スタンリーの「小笠原人(Bonin Islanders)だ」という主張を重く受け止めた。彼の島での活動のあり方を決定づけたのは、まさにこの一言だった。その後長沢は、時間をかけて島民のことを知った上で誠実なポートレイトを撮ることや、島民の個人史やコミュニティーの歴史を把握しておくこと、そして彼らのホームであるボニン・アイランズについて理解することの大切さに思い至る。彼は小笠原諸島の歴史について、出版物からだけでなく口述史からも可能な限りのことを学ぶことにし、多くの島民と対話を重ね、個人やコミュニティーの歴史について教わり、彼らのホームであるボニン・アイランズについて理解を深めていった。

長沢が島民に受け入れられるようになった背景には、歴史の理解以外にも理由があった。彼は写真を撮るために、コミュニティーの個人個人と相互協力関係を築いたのである。その結果は、彼は単なる「被写体」ではなく、言うなれば「写真パートナー」と呼べる人物たちのポートレートを制作することに成功した。同時に長沢は、単に美しいだけではなく、島民にとって重要な意味を持つ場の撮影も始めた。土地土地の歴史は、ちょっと覗き見にやって来た程度の部外者には開かれていない。長沢の写真は、小笠原人のアイデンティティーや歴史、そして彼らの命についての何がしかを、我々に伝え見せてくれる。

長沢の小笠原の写真は、はっきりと今日的である感性と、初期の写真には見られなかったような写真家と被写体の全く新しい関係性の上に成り立っている。プロジェクトを進めるにつれ長沢は、「日本人写真家」として、小笠原写真を巡る複雑な歴史や遺産を考慮に入れるだけではなく、相互信頼・相互理解をベースに島民と新しい関係を築いた上で撮影に臨む必要がある、ということに気づいた。ポートレイトの撮影には「写真パートナー」の同意と協力が不可欠だ。今や形勢は完全に逆転し、小笠原人の方にこそ、外部からの写真家による写真撮影を受け入れるか否かの決定権がある。辛抱強く島民との間に有意義な関係を築き、彼らの歴史やアイデンティティーについて理解を深めたことで善循環が起き、長沢は島民や彼らの大切にしてきた場の、より豊かで誠実なポートレイトを撮ることができた。写真家と島民の相互協力の結果が、この写真集だ。この本に収められた膨よかで外連味のないポートレイトは、小笠原人たち「を」ではなく、彼ら「と」撮られた珠玉の作品である。

Nagasawa’s Ogasawara

David Odo, DPhil.

Director of Academic and Public Programs and Research Curator Harvard Art Museums

The photographs in this volume represent well over a decadeʼs work by the Tokyo-based photographer Nagasawa Shinichiro in Japanʼs Ogasawara Islands, also known in Western languages as the Bonin Islands, a stunning group of over 30 islands located about 1,000 kilometers south of Tokyo. The subtropical archipelagoʼs natural beauty has attracted many visitors from Japan and all over the world to its shores, and in 2011 it was designated a natural World Heritage Site by UNESCO – one of only four in Japan – in recognition of its unique and fragile but well-managed environment. Its wealth of ecosystems is home to many endangered flora and fauna, including the Bonin Flying Fox (a fruit bat), and many endemic birds and plants. The seas surrounding the archipelago are teeming with numerous species of coral, fish, whales, and other aquatic life.

Although some of Nagasawaʼs images indeed feature the natural environment, his work is not merely a series of beauty shots of beaches and flowers. Rather, his pictures embody his deep engagement with both the people and places he has been visiting and photographing since 2008. He initially became fascinated by Ogasawara in 2007 after reading in a Japanese travel magazine about a community of “Western Islanders” (as they are often called) in the Islands who trace their heritage to 19th and early 20th-century pioneering settlers from outside of Japan. Although the islands were previously known to European, Japanese, and later, American sailors and whalers, they were first permanently settled by an international group of people from the Pacific, US, and Europe, who sailed from Honolulu in 1830 to establish a whaling colony in the then-uninhabited archipelago. The colony was organized in Honolulu and ostensibly founded under the auspices of Great Britain, but was a de facto independent territory and therefore without the military protection of a powerful country, which made it vulnerable to frequent attacks by pirates in its early years. Subsequent settlers migrated to the Islands from other parts of the world, including Japan, and it was taken over by Japanʼs emerging modern nation-state in the 1870s. Fierce battles between the US and Japan were fought in the Islands during WWII, they were seized in 1944 and occupied by the US Navy after the war, before they were finally reverted to Japanese control in 1968. The Islands are now administered by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and constitute one of the capitalʼs (very) far-flung island villages. Today, Ogasawara is an ethnically diverse community embedded within a larger Japanese society typically (but incorrectly) described as homogeneous. Itʼs no surprise that Nagasawa wanted to learn more about the Islanders, whose story remains little-known to outsiders.

In February of 2008, Nagasawa set out to visit the Islands aboard the Ogasawaramaru, the ship that sails between Tokyo and the port of Futami on Chichijima (“Father Island,” formerly known as Peel Island), the seat of the village government and the home of about 2,000 (out of fewer than 2,500 total) Islanders. The journey aboard the 1,000 passenger ship typically takes about 25 hours. The boat docks at Futami for a few days, turns around and sails back to Tokyo, and does it all over again. There is no commercial airport in the Islands, and this is the only regular mode of transport to the Japanese mainland. Ogasawara time is often measured in boats, the equivalent of a few days. Visitors will often be asked if theyʼll be staying for one boat or longer. Nagasawa excitedly made his way to Ogasawara with a plan to stay for three boats, which he thought would leave plenty of time to introduce himself to members of the Western Islander community and take photographs of them. Things did not go as he expected, however.

The first person Nagasawa sought out was Stanley Minami, the owner and captain of a whale watching boat. Nagasawa introduced himself to Mr. Minami shortly after arriving on Chichijima and told him he was interested in learning about the history of the “Western indigenous people” of the Islands and wanted to take pictures of them. He was promptly admonished to “Get lost – we arenʼt here for you to stare at. We arenʼt Americans. We arenʼt Japanese. We are Bonin Islanders! Donʼt come around here to take pictures just because you are curious!”

This was not an auspicious start, but it nevertheless turned out to be an important lesson for the photographer. Nagasawa walked away from that first, discouraging encounter understanding that this would be a far more complicated and lengthier project than he had originally thought. Fortunately, he soon met others who were willing to talk with him, some of whom even allowed him to take their pictures. They hinted that there was a troubling history of photography in the Islands, including a few cases in living memory where Western Islanders were treated like specimens or objects for scientific study rather than full human beings. One project in particular – conducted by a German geneticist initially in 1927 with a follow-up study in 1957– focused on producing photographic evidence of “race mixing” or “crossbreeding” and phenotypic expression, emblematic of the scientific racism of the era. This study rankled members of the older generation who remembered it personally and those who had heard about it from older relatives and friends who were directly subjectedto it. Photography was deeply implicated in this study, and clearly left a lasting bad impression in the minds of many Islanders. But it was neither the first nor the last (mis) use of photography to create a distrust of the medium among the Bonin Islanders.

The history of photography in the Islands dates to some of the earliest years of Japanese – Islander interactions. The first photographs were produced during Japanʼs 1875 – 1876 colonial expedition to the Ogasawara Islands, which followed a previous, short-lived, unsuccessful attempt to take over the settlement in 1862, toward the end of the Edo Period. (No photographs were produced during this expedition.) The successful Meiji expedition resulted in Japanese rule in the Islands that lasted until the late stages of WWII (resuming in 1968 and continuing to the present day), and was the first Japanese government colonial expedition to include an officially commissioned professional photographer, the Tokyo-based commercial photographer, Matsuzaki Shinji. As an expedition photographer, Matsuzaki created photographs for government information gathering purposes as well as commercial sale to the Japanese public. The landscapes and especially images of the Bonin Islanders created during the expedition read as visual information about Japanʼs new colonial possession – its land and human subjects – made for bureaucratic purposes, rather than as thoughtful or intimate portraits. We can only speculate about the exact conditions of production of these first photographs, but the colonial context suggests that the Islanders would have had little agency in deciding how – or even whether – the pictures would have been made.

After Japanese control of the Islands was firmly established, the government, scientists, media, and others undertook further photography projects, some of which were ostensibly organized to study the native flora and fauna, but which often included some images of the Islanders, especially the Western Islanders. An album of photographs was prepared for the Taisho Emperor in which many pictures of Islanders were included, and some of which were captioned with othering or racist and language. One image of a mother and child was said to show “Naturalized South Seas Barbarians” (nanʼyō doban kikajin). Western Islanders were frequently featured in picture postcards of Ogasawara produced in the first decades of the 20th century, and were typically shown as exotics, set apart from Japanese settlers. As the war encroached ever closer to Ogasawara and as the outlook appeared increasingly dangerous, the Japanese government evacuated civilians to the mainland in 1944. However, members of the Western Islander community (and their Japanese spouses/children) petitioned American authorities in 1946 to be allowed to return to Ogasawara, after having suffered terrible discrimination as “foreigners” in Japan,as they were easily identified with the American enemy despite their Japanese nationality, and suffered severe wartime and immediate postwar deprivation, as the entire country struggled to feed, clothe, and house its devasted populace.

As the US and Japanese governments were preparing the Islands to be returned to Japanese control in 1968, one village elder proclaimed in a newspaper article that he feared the Bonin Islanders would be come “South Seas Ainu,” meaning that he did not want the community to be othered or exoticized by the Japanese government or future visitors. There was a very rational fear that photography could be mobilized to objectify community members.

Over the years, many other incidents of photographs being taken of Western Islanders without their permission (or compensation) occurred, which naturally resulted inmany peopleʼs distrust of camera-wielding outsiders. Nagasawa was not aware ofthis history when he stepped off the boat in Futami harbor, but took to heart Stanley Minamiʼs proclamation of his identity as a Bonin Islander. This understanding shaped Nagasawaʼs approach to working in the Islands. He realized that he had to attempt to make true portraits of people by getting to know them well over time, learn about their personal and community histories, and come to an understanding of their home, the Bonin Islands. He set about to learn as much as he could about Ogasawaraʼs history, not only from published sources but also oral history, talking with as many people as he could, learning about their personal and community histories, and coming to an understanding of their home, the Bonin Islands.

This contextual understanding is not only what made it possible for Nagasawa to be allowed access to community members. It means that he was partnering with individuals in the community in order to successfully photograph them. It made it possible for him to create portraits with what I would call “photographic partners” rather than “subjects.”

Nagasawa also started to take pictures of places that he learned had local meaning – not merely because they were attractive. These histories are not always accessible to those of us on the outside looking in, but the photographs communicate something about the Bonin Islanders identity, history, and indeed lives.

Nagasawaʼs Ogasawara images reflect a distinctly contemporary sensibility and profoundly new relationship between photographer and subject than was evident in early photographs of the Islanders. As Nagasawa developed this project, he came to understand that his own identity – as a Japanese photographer – required him not only to acknowledge the difficult history and legacy of photography in Ogasawara, but to actively create new relationships built on mutual trust and understanding. In order to make successful portraits, he needed to collaborate with willing partners. The tables had turned completely, and the Bonin Islanders now had the power to refuse

or grant permission to the visiting photographer. Nagasawaʼs persistence in building meaningful relationships with the Islanders and his developing understanding of their history and identity started a virtuous cycle that allowed him to create richer and more authentic portraits of people and the places that hold meaning for them. The result of these collaborations is the set of photographs you will view in this book: a rich and honest portrait, created with Bonin Islanders, not of them.